From Raphael

to Bernini

History of a Collection

The Monumental Complex of San Francesco in Cuneo welcomes you to the exhibition The Borghese Gallery. From Raphael to Bernini. History of a Collection, curated by Ettore Giovanati and the Borghese Gallery management, with the sponsorship of Intesa Sanpaolo and the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Cuneo.

The exhibition tour presents a selection of 19 works from the Borghese Gallery, seldom exhibited to the public, offering a panorama of artistic trends from the Renaissance to the Baroque. Alongside works by masters of the Venetian school like Titian and Jacopo Bassano, there are masterpieces from the Central Italian school, marked by the rigour of the draughtsmanship and the construction of perspective.

The Borghese collection is an important and virtuous example of collecting, an ancient phenomenon that, from the Renaissance onwards, took on a systematic form linked to the representation of power. Art collecting became a way of affirming social status and building a public image, bearing witness to the relationship of close dependence between power, culture and dynastic identity. In Rome in particular, collecting was also bound up with ecclesiastical politics: popes and cardinals used the arts to affirm the spiritual and temporal primacy of the Church. The Borghese symbolised a form of patronage that was marked by its systematic nature, with a collection of ancient and modern works, including sculpture and painting, sacred and profane.

Before embarking on the tour, you may wish to listen to the next commentary to find out more information about Villa Borghese, which houses these masterpieces.

The Villa Borghese

Located outside Porta Pinciana in the heart of the city, Villa Borghese takes its name from the Casino Nobile complex – the current the home of the Borghese Galley – built at the start of the 17th century around the ancient “vineyard” owned by the Borghese family from Siena. The rapid rise of the Borghese in Roman society culminated in 1605 with the election of Camillo as Pope Paul V, who launched a period of urban works and extraordinary collections. The central figure in this scenario, as well as in the diplomatic and ceremonial representation of the papal court, was the Pope’s favourite nephew, Cardinal Scipione Caffarelli Borghese.

The construction of Villa Borghese was begun in 1607 and continued until 1613 under the direction of Flaminio Ponzio. It was completed by Giovanni Vasanzio – the Flemish architect known as Jan Van Santen – in line with the examples of the sixteenth-century Villa Farnesina alla Lungara and Villa Medici al Pincio. The lightness of the structure, divided into projecting buildings connected by a portico, ensured its perfect inclusion in the natural environment, while the brightness of the façade, decorated with reliefs and ancient sculptures, mirrored on the outside the splendour of the artworks within. The beauty of the park, with its long, tree-lined avenue, is enhanced, in particular, by the first painting that greets visitors: a Landscape by the Dutch painter and draughtsman Abraham van Cuylenborch. From 1770 onwards, the Villa underwent a radical renovation of the décor, initiated by Marcantonio IV Borghese and carried out under the direction of the architect Antonio Asprucci. An array of painters and sculptors worked on the decoration of the rooms, making the Villa Borghese Pinciana a model of stylistic renewal at the European level. Cardinal Scipione’s collection of ancient archaeological sculptures was involved in the sale imposed in 1807 by Napoleon on Camillo Borghese. Conceived as a private museum far ahead of its time, Villa Borghese is an example of a symbolic and political language, aimed at representing the family’s power and prestige. The Gallery became the stage for an aesthetic vision, capable of bringing together the legacy of the Renaissance and the new demands of the Baroque.

The daughter of an artist, Lavinia Fontana is regarded as the first professional female artist, who went on to run her own flourishing workshop in her native Bologna and later in Rome. She began her career in her father Prospero’s famous workshop, a meeting place for Bologna’s most avant-garde intellectuals. In 1577, she married Giovanni Paolo Zappi, a painter and also her agent, the son of a rich merchant from Imola. Her first public commission came in 1584; before then, no artist anywhere in Europe had ever obtained a commission to create an altarpiece. In the same year, she completed the famous Portrait of the Gozzadini family, a manifesto of reflection on the role of women and the centrality of the family. With these early works, Lavinia took her place in the artistic panorama of Bologna, adding the production of small devotional works and landscapes to her portraiture. The real breakthrough came in 1589 with a commission to paint the Holy Family with the Sleeping Child and the Infant Saint John, intended for the El Escorial monastery on the orders of Philip II, which established her as one of Europe’s most esteemed painters.

Between 1603 and 1604, Lavinia moved to Rome with her family and obtained numerous commissions, both public and private, from cultured clients. Portraiture was the genre in which the artist excelled and she often depicted female nudes in a period when women were not allowed to study human anatomy. She created portraits of occasions and record, investigating the psychological and emotional aspects of her subjects. She later became the favourite portraitist of Paul V Borghese in Rome.

Thanks to her Flemish-style expertise in capturing details, a direct influence of her father’s taste for collecting, on one hand, and her love for encyclopaedic knowledge, on the other, she was admired by all. Lavinia Fontana was also ahead of her time from the point of view of the managerial and practical aspects of her career; she was skilled in cultivating powerful friends and contacts and she displayed great acuity in consolidating her client portfolio in order to ensure high-level commissions.

The Infant Jesus Asleep, 1591, oil on copper, 43 x 33 cm

Documented in the Borghese household from 1693 onwards, The Infant Jesus Asleep is a work painted by Lavinia Fontana in 1591. This is a variant in small format of the well-known painting of the Holy Family from El Escorial, in which the painter included the figures of Saint Elizabeth and two angels holding up the drapes of the canopy. The underlying message regards the Truth and is revealed by John’s gesture, which invites the viewer to approach and silently watch Jesus sleeping, implicitly involving the observer in an intimate and private setting, which perfectly reflects the Counter-Reformation climate of the period. The baby Jesus is protected by Elizabeth, young John the Baptist, Joseph and his mother, who is covering him with a very thin veil. The scene is framed by a small, refined setting, dominated by a sumptuous baldachin, the colour of which is in close harmony with the tart, shrill hues of the fabrics and clothes of the subjects, accentuated by the dark background and the use of the medium of copper.

The artist adopted a complex iconographic approach for the prestigious commission, taking as models Raphael’s Madonna of Loreto, Sebastiano del Piombo’s Madonna of the Veil and Michelangelo’s Madonna of Silence. Her father, Prospero Fontana, had also been familiar with the models of these great artists through various engravings. The work was probably carried out for Camillo Borghese who, in 1591, was in Bologna in the role of Vice-Legate, a position that allowed him to come into contact with many local artists, including Lavinia.

Painter, architect and archaeologist, Raffaello Sanzio of Urbino combined lyricism and monumentality, intimacy and universality in a fusion that profoundly marked the history of European art.

The son of an artist, he was initially trained by his father Giovanni Santi – court painter of the Duke of Montefeltro – before joining Perugino’s workshop, where he learned compositional harmony and the grace of figures. He soon obtained independent commissions and, in 1504, he created his first great masterpiece: the Marriage of the Virgin, which displays an entirely personal language. He later visited Florence, where he encountered the work of Leonardo and Michelangelo. In these years, he created mostly sacred works, marked by balance and human warmth. An emblematic example is the Baglioni Deposizione – now in the Borghese Gallery – which had originally been part of a polyptych for the church of San Francesco in Prato: this work marked the dramatic pinnacle of his youthful production.

In 1508, he moved to Rome, summoned by Pope Julius II to paint the frescos in the Vatican Palaces; in the Stanza della Segnatura, he painted The School of Athens, a manifesto of humanist thought and his capacity for monumental synthesis. Thanks to its enormous success, he obtained new commissions, including the subsequent rooms and the Hall of Constantine, which was completed by his pupils after his death. Raphael also decorated the Villa Farnesina for the banker Agostino Chigi, painting the famous Triumph of Galatea and supervising the stories of Cupid and Psyche. In 1514, on the death of Bramante, he was appointed superintendent of the construction of St Peter’s, thereby finding himself at the centre of Roman architecture. His last work, the Transfiguration, remained unfinished due to his premature death in 1520 yet encapsulates all his art: balance and harmony are found alongside drama and excitement, bearing witness to the continuous evolution of his artistic language.

Portrait of a Man, 1502-1504, oil on wood, 46 x 31 cm

Depicted with the torso facing forward and the head slightly turned to the right, in contrast with the direction of the gaze, the subject portrayed wears a black robe and his face is framed by long hair. He has a large dark beret that contrasts with the blue of the sky while the landscape in the background is barely visible. The work was not originally in its current form: this subject wore a larger hat and a heavy fur jacket, opened on a lace-trimmed shirt. First attributed to Perugino, then Raphael and, finally, Pinturicchio, the panel was restored in 1911, removing the traces of numerous overpaintings, which fortunately preserved the face and its extraordinary hues. The attribution to Raphael or his master, Pietro Perugino, remains the subject of a debate that divides critics. Two questions remain regarding this controversial work: its origin and the identity of the subject. From 1833 onwards, it was included among the masterpieces of the Flemish school in the Borghese collection and identified as a painting by Holbein. The small format accentuates the strictly frontal nature of the composition, suggesting influences of the echoes of Flemish painting common to that particular cultural context. The most recent investigations also confirmed the exceptional quality of the face, which remains the part of the painting least affected by the overpaintings and, therefore, the most intact.

Born around 1498 in Pieve di Cadore, a small town in the Dolomites in the province of Belluno, Tiziano Vecellio moved to Venice to stay with his uncle Antonio. His artistic training began in the lagoon city, initially in the workshop of Gentile Bellini and, thereafter, in that of the more famous Giovanni. On arriving in Padua in 1510, the painter received an important commission to paint the frescos of the Scuola del Santo, which attracted the attention of the highest circles of the Venetian Republic. In 1516, he was appointed the official painter of the Most Serene Republic, obtaining highly prestigious commissions and creating unrivalled masterpieces. Prominent among these are the Assumption for the Basilica dei Frari, Sacred and Profane Love in the Borghese Gallery and the Pesaro Altarpiece, featuring a revolutionary spatial layout and an innovative use of colour, which inaugurated an entirely new language in the Venetian painting of the day.

In the fifteen twenties, his fame spread beyond Venice: he worked for Alfonso d’Este in Ferrara and the Gonzaga in Mantua and struck up relationships with Pietro Aretino and Jacopo Sansovino, influential figures in the cultural life of the lagoon. In 1530, Aretino introduced him to the emperor Charles V, and Titian was appointed as his official portraitist. The portraits commissioned by the Habsburgs and, soon afterwards, also by the Spanish court of Philip II, introduced innovative models in the representation of power. Meanwhile, Titian continued to cultivate his relationships with the most important families of the peninsula.

From the fifteen forties onwards, his style became more dramatic and vigorous, with broad brushstrokes and intense colours. In his final decades, his painting took on an increasingly expressive and experimental nature, with dense chromatic mixtures and gestures that anticipated modern solutions. The works in this concluding phase were characterised by a tragic pathos and unprecedented technical freedom. Titian’s legacy, founded on the centrality of colour and the expressive power of light, would profoundly influence generations of artists, consolidating his renown and timeless success.

Portrait of a Dominican Friar (San Domenico), circa 1565-1569, oil on canvas, 97 x 80 cm

Part of the rich Borghese collection since 1693, this work displays the stylistic features of Titian’s later period. It depicts a subject, considered alternately to be Saint Dominic, Saint Vincent Ferrer or a Dominican monk, wearing the usual habit of the Order: white robe and black cloak. The ray of light that strikes the robe illuminates the right hand, caught in a symbolic gesture. The face is an example of the superb portraiture produced by Titian who, in the last years of his life, experimented with a completely new technique, a concise pictorial style that featured rapid brushstrokes with an almost impressionistic touch. The first mention of the painting dates from the early seventeenth century, when he was already in Rome. From the second half of the nineteenth century until after the Second World War, this work from Titian’s later period enjoyed critical acclaim. Specifically, the application of the brush was praised but, above all, the quality of the painting, which was a “truly lifelike“ portrait. Not surprisingly, another theory put forward concerned the identity of the subject: Titian’s Dominican Confessor. This identification was groundless. It was based on the firm character of the subject, his humility, the simple nature of the chromatic range – reduced to white, black and the dark ochre of the background – and the skilful alternation between light and shade. The Venetian painter, by then in his prime, used a simple palette: he eliminate the landscape and the background, allowing the preparation to partly emerge in order to concentrate on a face full of meaning, framed by the hood of the black cloak, which emphasises the well-defined features of a man mindful of his faith.

If you want to find out more about collecting between the Renaissance and the Baroque, listen to the following commentary.

Collecting between the Renaissance and the Baroque

Collecting objects is a very ancient practice but it was in the late sixteenth century that collectors began to appreciate artworks in relation to their creators, while also considering their market value. Vasari was the first to introduce the concept of historiography in collectors’ research; he offered his intellectual assistance to Grand Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici in creating a colossal art collection.

A new type of space dedicated to art sprang up in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries: the gallery. This originated in the classical world, in the atriums and loggias of Roman villas and residences. In the first half of the sixteenth century in France, galleries had an essentially recreational function, as covered walkways. In Italy, on the other hand, they became places for displaying artworks. By the end of the sixteenth century, the gallery had also become a customary accessory in all noble residences: in Rome, it acquired its most flamboyant and celebratory expression, the greatest example of which is the Borghese Gallery. Its evolution was very rapid: from a space dedicated to the collection of small objects to a stateroom for the noble and princely classes and, finally, a place to exhibit art. In Nordic countries, on the other hand, a notable aspect of sixteenth-century collecting was the Wunderkammer – Chamber of Wonders – that contained scientific, natural and artistic rarities.

The seventeenth century was the era of amateur collectors, who acquired artworks for pleasure, expressing a critical judgement, free of prejudice. Rome would become the artistic capital of Europe, home to major collectors of the calibre of Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte, Scipione Borghese, the Barberini, the Colonna and other noble families.

The son of the musician Daniele Reni, Guido trained initially in the workshop of the Flemish artist Denys Calvaert, before joining the Accademia degli Incamminati, where he absorbed the Carracci Reform, based on drawing and the study of the human figure and nature from life. On joining the workshop of Ludovico Carracci between the end of the fifteen nineties and the beginning of the new century, he took part in work on the Oratory of San Colombano, recorded by the sources as a glorious competition between the young artists of the Carracci circle like Albani and Domenichino. His personal breakthrough came in 1598 when he beat his own master in obtaining the commission to create the temporary decorations on the façade of the Palazzo Pubblico on the occasion of the entry of Pope Clement VIII in Bologna.

Between 1601 and 1614, he spent long periods in Rome. His first major commission came from Cardinal Paolo Emilio Sfondrati, who assigned to him the creation of a cycle of paintings for the church of Santa Cecilia in Trastevere. Later, Guido Reni encountered Caravaggio’s naturalism, depicting drama contained within a rigorous formal construction. In those years, his language was already tending to move towards a bright, measured classicism, which would become the painter’s hallmark. His growing success soon saw him working for the highest levels of Roman society. On returning permanently to Bologna, he created a number of works that would be highly-regarded models for seventeenth-century painting.

In the sixteenth thirties, his painting took on an increasingly clear nature, with rarefied, luminous figures. His later canvases, on the other hand, display a rapid and simplified approach. This acceleration may also have been linked to his economic requirements: a heavy gambler, the painter tended to accept numerous commissions to pay off debts. With his synthesis of naturalism and the classical ideal, the “divine” Guido Reni was a point of reference in European art, able to combine grace and monumentality in a unique, universal language.

Country Dance, circa 1601-1602, oil on canvas, 81 x 99 cm

The scene depicts a Country Dance, accompanied by the music of the lute and the ‘viola da braccio’, an early violin, organised by a group of peasants, in which a number of local ladies and gentlemen are taking part. The figures are sitting in a circle in a clearing among the trees, alongside which a stream flows. The gaze of the spectator lingers on the variety of the characters’ poses. In the background, a stretch of water crossed by some sailboats is illuminated by the twilight while some birds stand out against a dark and cloudy sky.

The identification of Guido Reni as the artist behind the canvas was one of the most important and unexpected discoveries of recent years, together with its documented provenance from the collection of Cardinal Scipione Borghese. In the early years of his Roman sojourn, the artist dedicated himself to the landscape genre, but only to a limited extent; it evolved in parallel with the development of figure and history painting, suitable for altarpieces and fresco decorations, practised since his youth. After the death of Annibale Carracci, Cardinal Scipione wanted to make him his court painter since he was by then the most important figure on the Roman artistic scene; he assigned to him the decoration of palaces and family chapels, which preserve the painter’s greatest masterpieces.

If you want to learn more about the new language of images, listen to the next track.

The new language of images

The language of images underwent profound change from the Renaissance to the Baroque, creating more complex, intellectual and sophisticated artistic forms that prepared the ground for the Baroque style, characterised by dynamism, theatricality, drama and attention to emotion. While the Renaissance sought balance and naturalism, the Baroque esteemed irrationality, eccentricity and surprise, through a visual language that aimed to astound and involve the spectator. With the Lutheran Reformation, the Catholic church was harshly criticised for its most flamboyant manifestations, the splendid ceremonies of the Curia, the mixing of the sacred and the profane that had transformed the Papacy into a worldly court. The dictates of the Council of Trent in response to the Protestant challenge were intended to promote a strict Counter-Reformation in order to bring the Catholic church back to authentic simplicity. Ancient construction sites were therefore reopened in Rome – like the Fabric of Saint Peter – alongside new ones, profoundly changing the urban layout and redesigning a “City of God” in the spirit of a Christian renewal. In this way, the typically Italian taste for the theatre and music was rediscovered and, above all, perfected, made magnificent and imposing as an instrument of the rebirth of the Church of Rome. The families of cardinals competed to recruit the best architects and painters to enliven Baroque Rome, for the restoration or decoration of their residences but also for the choreography of social events and liturgical celebrations. Rome was transformed into the great theatre of the world, thanks to the flourishing entertainment industry, which provided the finest artisanal and artistic talent of the grandiose Baroque period.

One of the most eminent figures of the seventeenth century, Gian Lorenzo Bernini was born in Naples in 1598 and moved as a child to Rome with his father Pietro, a sculptor from Tuscany. The city would become the absolute centre of his life and career. At an early age, he demonstrated an extraordinary talent for sculpture. His training was closely supervised by his father but the pupil soon surpassed the master in inventiveness and expressive force. His early works were commissioned by Cardinal Scipione Borghese: the sculptural groups of Aeneas, Anchises and Ascanius but, above all, The Abduction of Proserpina and Apollo and Daphne display his ability in imbuing marble with unprecedented dynamism and vitality.

With the election of Pope Urban VIII Barberini to the papal throne, Bernini established himself as an all-round court artist; he was not only a sculptor but also an architect and set designer. In this period, he created one of his masterpieces: St Peter’s Baldachin, the monumental bronze structure above the high altar of the Vatican Basilica. The work, along with the iconic design of the Colonnade of Piazza San Pietro, radically changed the appearance of the heart of Christianity, bestowing on the basilica a grandiose and theatrical style, able to express in visual form the idea of welcome and the magnificence of the Church.

After a difficult period under Pope Innocent X Pamphilj, Bernini regained the pontiff’s favour with the design for the Fountain of the Four Rivers in Piazza Navona. The work is a scenographic triumph in which architecture, sculpture and the movement of water merge in a spectacular fusion, transforming the urban space into one of the highest symbols of Roman Baroque. Bernini was also outstanding in the art of portraiture, combining psychological intensity and the stunning rendering of his models’ features.

Thanks to the prestige he gained in Rome, he also attracted the attention of European courts. Invited to Paris by Louis XIV, he designed the new facade of the Louvre in 1665 but his contribution was never taken into consideration by the sovereign. On his death, Bernini left an immense legacy. His ability to combine different arts made his language unique, the model for all Europe.

The Goat Amalthea, before 1615, marble, height 45 cm

This sculptural group had certainly become part of Scipione Borghese’s collection by 1615, the year in which payment was made for the wooden pedestal that supported it. The subject portrayed was very well-known in ancient mythology: the newborn Jupiter, threatened with death by his father Cronus, is saved by his mother Rhea, who takes him to Crete. There, he is brought up by Amalthea, initially a nymph, later identified as a goat that suckles him. Ovid links the original myth to that of the goat’s horn – cornucopia – endowed with miraculous powers, given by Jupiter to his wet-nurses. Behind the goat, a small faun – identified as Pan – is drinking milk from a bowl. The work has been seen as an early example of the artist’s extraordinary gifts, although some critics dispute the attribution. The sculptor applies the classical technique of invention, presenting a well-known subject in a new and surprising way. The subject is laden with allegorical meaning connected to the cornucopia, suggesting the return of the Golden Age under the papacy of Paul V Borghese. Among the documents of the Borghese family, there is no record of any payment for the work, suggesting the possibility it was a gift for Scipione, as a sample of the prodigious technical abilities of an extremely young Bernini.

The use of the “unfinished” technique that would characterise the sculptor’s entire production appeared for the first time in this group. Some youthful uncertainty can be seen in the protruding or thinner parts of the sculpture, such as the horns, the goat’s tail and the rim of the cup. The crown of vine leaves and the presence of Pan introduce the extremely sensual nature of Jupiter, enriching the subject with an unprecedented moralistic meaning. References to the senses can also be recognised in the group: sight is introduced in the exchange of glances between the characters, the open mouth and the bell around the goat’s beck suggest hearing, taste is expressed by Pan drinking milk; finally, touch is linked to the action of milking, as well as the naturalistic rendering of the animal’s cloak.

If you want to find out more about the history of the Borghese collection over time, listen to the next track.

The Borghese collection over time

With the election of Paul V Borghese as Pope, his nephew, Cardinal Scipione Caffarelli Borghese commissioned a very extensive series of architectural projects, at the same time launching the systematic acquisition of artworks that would make his collection one of the largest of the period. In 1607, through the seizure of paintings from the studio of Cavaliere d’Arpino, who had been involved in legal proceedings, the cardinal took possession of around 100 paintings. In particular, he set his sights on the youthful works of Caravaggio, such as the Young Sick Bacchus and the Boy with a Basket of Fruit.

The cardinal’s extreme unscrupulousness in securing artworks and indulging his passion as a modern collector is confirmed by numerous episodes, such as the purchase of Caravaggio’s Madonna and Child with Saint Anne in 1605, which was rejected by the Confraternity shortly before it was to be displayed in the chapel of Saint Peter’s, perhaps on the orders of the Pope himself. The most famous example of this unscrupulous attitude is the audacious theft of Raphael’s Deposition, illegally seized by Scipione’s emissaries from the Perugino convent of San Francesco al Prato, lowering it from the walls of the city during the night of the 18th and 19th of March, 1608. It was later described as “a private matter of the cardinal’s” by Paul V.

The collection of ancient sculptures was also constantly being enriched, through purchases but also thanks to extraordinary occasional discoveries, such as in the case of the Gladiator – now in the Louvre – and the Hermaphrodite, found during excavations near the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome. On the orders of the cardinal, all his assets were subject on his death to a very strict trusteeship, a legal status that preserved the integrity of the collection throughout the 18th century.

By the end of the seventeenth century, the Borghese owned around 800 paintings and one of the most celebrated collections of antiquities in Rome, in addition to a vast property portfolio. The archaeological collection excited the interest of Napoleon Bonaparte; his sister Pauline had married Prince Camillo Borghese, who was ordered by the emperor to sell him the sculptures between the end of 1807 and 1808, which were transferred to the Louvre, where they remain today. Two of the Villa’s most famous masterpieces are linked to Camillo: the statue of Pauline Bonaparte as Venus Victrix by Antonio Canova and Correggio’s Danaë. In 1883, the prince renewed the trusteeship, which remained in place until the Museum and Gallery were bought by the Italian state in 1902.

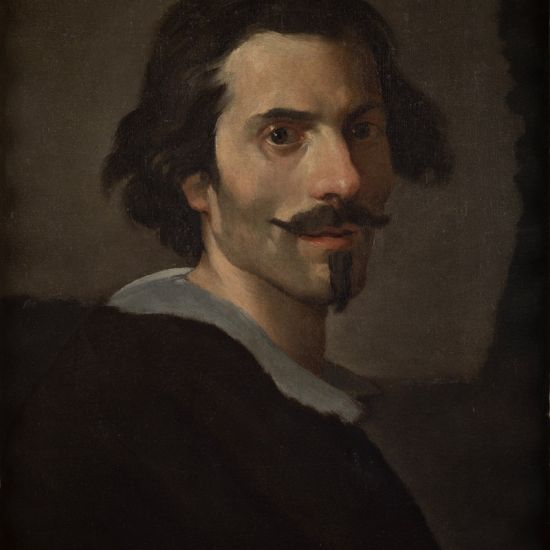

Self-portrait at a Mature Age, circa 1635 – 1640, oil on canvas, 53 x 43 cm

Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Self-portrait at a Mature Age became part of the Borghese collection in 1911, thanks to a donation by the German Baron Otto Messinger, who presented it to the Museum as a mark of his love for Italy. The attribution of the painting to Bernini has never been disputed by the critics but there are many suggestions concerning its dating. Due to the style and apparent age of the artist – around forty years old – the self-portrait can be convincingly traced back to the second half of the sixteen thirties. The canvas reveals the signs of age: the face is thinner, the hairline is slightly receding, there are circles around the eyes and a few white hairs in the hair. The dark outfit with the white collar are barely sketched, similar to other portraits and typical of the artist’s habit of focusing mainly on rendering the face, its physiognomy and expression. However, in this case, the entirely incongruous brushstroke near the ear, which interrupts the uniformity of the barely visible beard, suggests the unfinished nature of the painting, perhaps due to fatigue or the artist’s dissatisfaction with the progress of the work. The great notoriety of the painting, perhaps the most representative of Bernini’s self-portraits, is also due to the fact it was on public display since it was printed on the Italian 50,000 lire banknote. According to critics, it is an evolution in Bernini’s portraiture compared to known examples from the sixteen twenties, evidence of a style by then free of the influences of other masters and furnished with its own specific identity, worthy of direct comparison with Renaissance portraiture.

The journey of discovery of the Borghese collection has come to an end. Thank you for listening and see you soon!